VW-1's TYPHOON TRACKERS -

TURNING PACIFIC WEATHER INSIDE OUT

Each morning on his flagship, Vice Admiral Paul P. Blackburn, Jr., Commander Seventh fleet, is briefed by his staff.

At the same time the commanders of Seventh Fleet task forces are being briefed by their staffs.

A VW-1 Warning Star takes off from Naval Air Station Sangley Point P.I. on another mission

A VW-1 Warning Star takes off from Naval Air Station Sangley Point P.I. on another mission

Pilots of aircraft are briefed before being launched from the decks of giant carriers or taking off from air bases.

All these briefings, whether they concern the movements of a fleet, a bomb-laden aircraft headed for North Vietnam or a destroyer steaming toward a rest and recreation port, have one thing in common -- weather.

Weather briefings are so detailed and forecasts so accurate that ships can change course long before reaching heavy weather. Pilots can program flights with the assurance they won't hit a storm.

How can these forecasts be made in the vast Pacific where several typhoons may be moving in different directions while dangerous tropical storms work up to typhoon force?

They are made possible through data collected by weather reconnaissance squadrons like the Navy's Guam based Airborne Early Warning Squadron ONE (VW-1).

In 1964 VW-1 flew 54 percent of the Western Pacific weather flights.. Since being assigned its typhoon tracking duties in 1961, the squadron's EC-121K Warning Stars have tracked more then 90 typhoons.

Electronics Technicians and Aerographers Mates work together to assemble the Dropsonde. As they drop to the

surface by parachute, these battery powered transmitters send back signals which give the meteorologist a

picture of the storms vertical structure.

Electronics Technicians and Aerographers Mates work together to assemble the Dropsonde. As they drop to the

surface by parachute, these battery powered transmitters send back signals which give the meteorologist a

picture of the storms vertical structure.

In competition with all other Navy units, VW-1 has won the U. S. Naval Weather Service Outstanding Performance Award for 1962 and 1963 and is nominated for the 1964 award.

Six VW-1 crews of 23 men, including a meteorological officer and two enlisted weather specialists on each crew, are available to fly weather flights at any time in the Seventh Fleet area. This 30 million square mile expanse runs from the international dateline to the Indian Ocean and from the Equator to the Bering Sea.

Any day may find VW-1 aircraft working out of bases in Japan, Okinawa, Taiwan the Philippines or its home base on Guam.

Possible storms may be discovered by a number of ways. A ship's barometer may register low, a civilian pilot may notice some threatening clouds, radar pictures from weather satellites may reveal suspicious formations. (While orbiting the earth in Gemini 5, astronaut Gordon Cooper reported a tropical depression which was located by VW-1 on August 28.)

Anything looking like a brewing storm in the Western Pacific is reported to Fleet Weather Central/Joint Typhoon Warning Center (FWC/JTWC) on Guam.

FWC/JTWC then directs the Tropical Cyclone Reconnaissance Coordinator (TCRC) at Andersen Air Force Base, Guam to assign trackers to the storm. TCRC coordinates the efforts of VW-1and the Air Force's 54th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron at Andersen AFB and the 56th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron at Yakota Air Base in Japan.

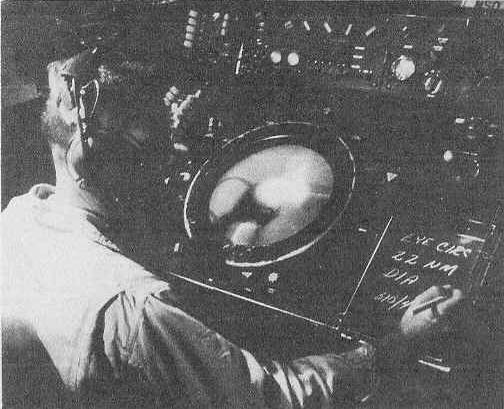

Using the radar presentation a weather specialist measures the eye of a tropical cyclone.

Using the radar presentation a weather specialist measures the eye of a tropical cyclone.

The task of getting fixes (positions) on storms every six hours is then assigned to the squadrons. VW-1 makes the night fixes because of the Warning Star's sensitive radar. Occasionally they must make both day and night fixes when other squadrons are unable to fulfill their commitments.

In four years VW-1 has failed to meet only one commitment. That was in 1964 when they flew 316 of 317 assigned missions.

With the Warning Star's ability to stay airborne for 20 hours, they can make 2 fixes, six hours apart, on a storm in one mission.

"We've even made quadruple fixes," said LT F. E. Horn of Stanford, Fla. He is one of 7 flying meteorological officers assigned to VW-1

The 35-year-old veteran of 17 years naval service told how, in 1964 his squadron made two fixes on both tropical storm Marie and typhoon Kathy in a single mission. The storms were between Okinawa and Japan.

To make a fix the eye of the storm must be found. This is done by flying into the storm's center to find the area of lowest pressure. Subsequent fixes show the direction and speed in which the storm is moving. This makes forecast possible.

Lt Horn said the storms start as tropical cyclones (33-knot winds or less). "Some of them don't even have clouds we can see on radar, so we fix the depression by visually locating the center of the cyclonic wind flow on the ocean surface and taking pressure readings," he said.

AG3 R. R. Rowan works with Lt. F. E. Horn to draft a weather report containing the storm's position, pressure

and other pertinent data.

AG3 R. R. Rowan works with Lt. F. E. Horn to draft a weather report containing the storm's position, pressure

and other pertinent data.

As soon as the fix is made the aircraft radioman sends the cyclone's position, wind velocity, pressure and other pertinent data to the nearest air to ground communications station Clark AFB in the Philippines, Andersen AFB on Guam or Fuchu Air Station in Japan). The information is immediately relayed to the Joint Typhoon Warning Center on Guam.

Four times daily when tropical cyclones exist, JTWC issues warning to all ships and weather stations in the Pacific. These are scheduled between fixes so the latest information is seldom more then three hours old.

Even in the case of a full-blown typhoon the storm must be penetrated to get an accurate fix. This may mean flying into storms of more than 100-knot winds.

Penetration is usually made at 1500 feet or lower, said Horn, because the air is less turbulent at that altitude.

The meteorologist looks for a feeder band (curved bands of heavy clouds, as much as 300 miles long, feeding into the storms center) on radar. Between these bands is an area of relatively smooth air, said Horn.

With this feeder band presentation on radar the meteorolgist and the combat information officer (a radar specialist) vector their aircraft toward the cyclone's center.

The Warning Stars have a galley where crewmen cook hot meals during their long hops.

The Warning Stars have a galley where crewmen cook hot meals during their long hops.

The record proves their good judgement. VW-1 has 94,000 accident-free hours flight hours dating back to its origin in 1952.

"The force of a typhoon is inconceivable," said Horn. "A wrong step and a severe typhoon could turn our plane upside down and beat it up in pieces before we knew what was happening," he said.

Height-finding radar, used with search radar, enables the meteorologist to avoid hard-core centers in feeder bands and other severe weather.

Horn told of an east coast weather plane that tangled with an Atlantic hurricane. The aircraft's structure was badly damaged and some of the crew was injured by being tossed around, he said.

"The typhoons we have in the Pacific are basically the same as the Atlantic hurricanes." said Horn.

To get more information on a typhoon, the VW-1 weather planes drop a battery powered radio transmitter called a Dropsonde. These are ejected in the eye and each quadrant of the storm and as they descend by parachute the signals received in the aircraft give the meteorologist a picture of the atmosphere's vertical structure. It is a reversal of the weather balloon.

A feature of the EC-121K Warning Star which could save a ship which may get too close to a storm is a radar system through which the storm's presentation can be relayed to a ship's radar.

The Joint Typhoon Warning Center also sends forcasts to all weather stations in the Western Pacific alerting civilians when a typhoon is heading toward a populated area.

Some of VW-1's missions turn out to be minor cyclones that run aground before they build to storm intensity, but, said meteorologist Horn, "We would rather be safe than sorry."