IT WAS TIME TO GO. As green water smashed the glass windscreen of the destroyer, LCDR James A. Marks, USN, commanding officer of USS Hull (DD 350), stepped off the bridge into the sea. He was but one of a handful of Hull men who survived.

Hull was one of three destroyers which capsized and sank that day, 18 Dec 1944, as the Third Fleet encountered in the Philippine Sea one of the worst storms in the history of the Navy. More damage was inflicted than by any other storm since the famous hurricane at Apia, Samoa, in March 1889. In addition to the loss of three DDs, four light carriers, three escort carriers, five destroyers, two escort destroyers, one light cruiser and one Fleet oiler were among the ships damaged. A total of 146 airplanes were lost, including eight blown overboard from battleships. The lives of almost 800 personnel were lost..

STORMS HAVE PLAYED an important role in the history of sea warfare when, on the day of battle, the ships couldn't run away.

The Greeks (and a storm) won an important victory over the Persians when the storm broke up the Persian fleet off the promontory of Mount Athos in 492 B. C. Dirty weather, as well as Drake, helped defeat the Spanish Armada and then, after the battle, helped destroy what was left of the Spaniards off the coast of Ireland. The Japanese homeland was saved from invasion in 1281 by a "Divine Wind" which shattered a powerful Mongol fleet of Kublai Khan.

Another "divine wind" almost, but not quite, again saved Japan in the more recent past, when elements of the Third Fleet, preparing for attack on the Philippines, were struck by a typhoon.

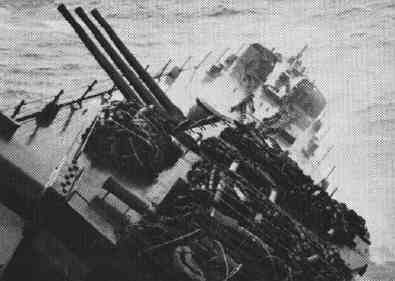

Task Force 38 at this time was composed of seven Essex-class and six light carriers, eight battleships, four heavy and 11 light cruisers, and about 50 destroyers. The fuel supply of many of these ships, particularly the destroyers, was dangerously low following a three-day strike on Luzon.

THE SEA WAS MAKING up all day but the waves were from the same direction as the northerly wind (which was not above 30 to 40 knots). Wind and sea, however, had already made refueling difficult.

USS Maddox (DD 731), a new 2200-ton destroyer, required three hours' work to obtain 7000 gallons from the oiler Manatee. The hose then parted and she had to cut the towline, narrowly avoiding a collision. Two hoses parted on New Jersey when she tried to fuel the destroyers Hunt and Spence.

The escort carrier Kwajalein (CVE 98) one of the replacement-plane CVEs that belonged to an oiler group, was unable to transfer pilots by breeches buoy, and canceled air operations at noon. Her deck crew then concentrated on respotting and relashing planes, which were secured three ways with steel cables. It was too rough for escort carriers to recover CAP (combat air patrol). Two planes still aloft at 1500 were flagged off from their respective carriers and their pilots were ordered to bail out. They were rescued by a destroyer.

At sunset, a sinister afterglow remained in the sky. The sea was deep black except where the wind whipped off wave crests into spindrift. On board Kwajalein, then heading almost dead into the wind, as each wave rolled under, the entire bow would come out of the water, hover for a few seconds, and then crash, taking the flight deck almost to sea level. Plates were clanging and snapping, and ripples ran up and down the steel hangar deck. The forward lookouts, normally stationed in the catwalks, were ordered to secure. Because of the mounting seas, zigzagging was canceled after sunset.

By 0800, Kwajalein had to heave to and, with both engines ahead full and with wind on the starboard bow, made a few knots leeway. Salt water was blowing horizontally at bridge level. There seemed to be no separation between sea and sky. The sound of the wind in the rigging, especially in the large radar bedspring, was frightening. The battle ensign was reduced to a small scrap showing two stars.

BY THE AFTERNOON of 18 December, Task Force 38 and its fueling groups were scattered over a space estimated at 50 by 60 miles. Except for the battleships, all semblance of formation had been lost. Every ship was laboring heavily; hardly any two were in visual contact; many lay dead, rolling in the trough of the sea; planes were crashing and burning on the light carriers.

From the islands of the carriers and the pilothouses of destroyers, men looked out on a scene they had never seen before and which few of them would ever see again. The weather was so thick that sea and sky seemed to form one element. At times the rain was so heavy that visibility was limited to three feet, and the wind so strong that, to venture out on the flight deck, a man had to crawl on his belly.

Occasionally the storm-wrack would part for a moment, revealing escort carriers crazily rising up on their fantails or plunging bow under, destroyers rolling drunkenly in hundred-degree arcs or beaten down on one side.

The big carriers lost no planes, but the extent of their rolls may be gauged by the fact that Hancock's flight deck, 57 feet above the waterline, scooped up green water. The battleships took the seas without strain, but the cruiser Miami (CL 89) took a series of heavy seas that buckled her shell, main deck and longitudinals from the stem to about frame 22.

The light carriers had a bad time because the rolling and pitching caused plane lashings on hangar decks to part, and padeyes to pull out of flight decks. Planes went adrift, collided and burst into flames. Monterey caught fire at 0911 and lost steerageway a few minutes later. The fire was brought under control within half an hour and the commanding officer decided to let the ship lie dead in the water until temporary repairs could be made.

Monterey lost 18 aircraft burned in the hangar deck or blown overboard and 16 seriously damaged. Cowpens lost seven planes overboard and caught fire from one that broke loose. However, the fire was brought under control promptly. Langley rolled through 70 degrees; Sun Jacinto had a plane become adrift on the hangar deck which wrecked seven others. She also suffered damage from salt water that entered through punctures in the ventilating ducts.

SO MUCH FOR THE big picture. What about the destroyers Hull, Spence and Monaghan, that were lost? Here is the story of Hull as told by her commanding officer, LCDR Marks:

"I have served in destroyers in some of the worst storms in the North Atlantic and believe that no wind could be worse than that I have just witnessed."

"Shortly after twelve o'clock the ship withstood what I estimated to be the worst punishment any storm could offer. She had rolled about 70 degrees and righted herself just as soon as the wind gust reduced a bit. Just at this point the wind increased to an estimated 110 knots. The force of the wind laid the ship steadily over on her starboard side and held her down in the water until the seas came flowing into the pilothouse."

"The ship remained over on her starboard side at an angle of 80 degrees or more as the water flooded into her upper structures. I remained on the port wing of the bridge until the water flooded up to me, then I stepped off into the water as the ship rolled over on her way down. The suction effect of the hull was felt but it was not very strong. Shortly after, I felt the concussion of the boilers exploding under water. I concentrated on trying to keep alive."

A TOTAL OF SEVEN officers and 55 enlisted men survived. Most were rescued by uss Tabberer (DE 418) through a million-to-one fluke. The storm, which at this point reached a velocity of 122 knots, had ripped away her mast and radio antennas and a radioman had gone on deck during a lull in the storm to repair the antennas.

Looking out over the water he saw a dim light on the surface and at once yelled, "Man overboard!" A man from Hull was pulled aboard. Instead of rendezvousing with the fleet, as had been her plan, Tabberer continued hunting for survivors of Hull, which was now known to have foundered.

The captain of Tabberer ordered the ship's searchlights to be turned on, knowing that there was no danger of attack by Japanese submarines in a sea like this, and had cargo nets dropped over the side to make it easier to bring survivors aboard. During the night he picked up 12 more men from Hull and the next day, 19 December, Tabberer found Hull's commanding officer who was so weak he had to be dragged aboard.

During the afternoon another officer from Hull was sighted floating about 60 feet from Tabberer, but even nearer was a large shark, which was apparently waiting for an opportune moment to attack. Men on Tabberer called to the officer to swim to the ship, while they began firing tommy guns to scare the shark away, but the officer was too exhausted to swim and the shark did not frighten easily. Finally, the ship's executive officer, LT Robert M. Surdam, USNR, dived in and brought the officer to the ship.

Later the same day, Tabberer found a group of seven Hull men clinging together, although they had been in the water for over 26 hours. One of the men had been the entire time in the water without a lifejacket, but he climbed aboard without assistance.

YET HULL WAS RELATIVELY LUCKY. Only 24 men were saved from Spence.

On 17 December, Spence (DD 512) prepared to refuel and so pumped out all the salt-water ballast in preparation for the job, making the ship less stable than under normal circumstances. Rough seas, however, prevented the ship from taking on additional fuel and the next morning, to conserve her dwindling 24hour supply, she cruised to the east of Luzon with only one boiler in use. By ten that morning the ship was trapped in canyon-like troughs of sea water. The electrical board began to get wet from taking great quantities of water aboard in the continuous rolling of the ship.

After she went into a 72-degree roll to port, all the lights went out and the ship's pumps stopped. Her steering controls became damaged and she floundered helplessly on her port side. Mountainous waves swept the deck and tore lifeboats and rafts from their moorings.

Spence flopped completely over at about 1100 on 18 December. This is how Spence's supply officer LT A. S. Krauchunas, USNR, saw it:

"I sat on the edge of the bunk in the captain's cabin, discussing the seriousness of the storm with Doc, when a terrific roll threw me on my back against the bulkhead amid a shower of books and whatnots. On hands and knees I desperately made my way along the bulkhead until I dropped through a door leading into the narrow passageway which led to the main deck. From the light filtering through from above, I saw oily water rushing to engulf me. Turning, I saw a light shining down from the radio shack passageway. I scrambled up the width of the ladder and fled through this corridor. The water followed me, sealed off the radio shack passageway and trapped all below."

"There was no orderly jumping overboard, no systematic lowering of lifeboats or rafts - they had been torn from their moorings-but a matter of swimming desperately from the ship that was about to turn completely over."

"Approximately 70 men got off the ship, mainly from topside, the torpedo and radio shacks, bridge and passageways. Men began to collect from all directions until we finally had a group of 20 or so on our floater net. Time and again it was washed violently against the side of the ship by the action of the waves. We kept pushing ourselves off the port side of the ship until finally the net was freed."

Within five minutes their net was alone. Crowded with men, the net would ride three or four of the towering waves, only to have the next one break over them. Tons of water would drag them below the surface. One by one, as the men poked their heads through the waves, they would find their net 20 to 40 feet away and, in the fight to swim back, a few would fail to reach the net. Eventually, the group was whittled down to nine.

BY THE AFTERNOON of 18 December, the storm had moderated, and an inventory was taken of supplies aboard the net. Food and medical kits had been torn away, but a kit of flares, a hatchet and two water kegs were found. During the afternoon the two water kegs repeatedly broke away from the net and each time were recovered by LT Krauchunas and Water Tender C. F. Wohlleb.

On the morning of 19 December the men had their first drink. At 1000 a search plane was spotted about eight miles away. One of the dye markers was used but the plane did not see it. That afternoon they sighted an overturned table floating in the water. For nearly two hours they swam, pulling the net with them, during which time the distance between them and the table narrowed to 100 yards.

By nighttime, J. P. Heater, Seaman First Class, who had been injured when the ship was lost, became unconscious and Wohlleb devoted his energies to keeping him on the net. LTJG John Whelan had been drinking salt water and was somewhat dazed, while the steady drain on the vitality of ENS George W. Poer was beginning to show. He would float away from the net and the men would shout, causing him to turn and swim back, exclaiming "Where have I been?" Poer repeated this twice and then, about 2300, floated away for the last time.

LTJG Whelan had lost consciousness by now and LT Krauchunas and Quartermaster Edward F. Treceski took turns holding him. Heater died.

DURING THE EARLY MORNING hours of 20 December, one of the water kegs broke loose and during the effort tb recover it, LTJG Whelan disappeared from the net, leaving only six of the original 20.

In the distance, flashes of light were again seen on the horizon. After a time they saw an escort carrier bearing down upon them. Its shape coula be seen silhouetted against the sky along with shadowy forms of men at work on the flight deck. They yelled, but she disappeared into the darkness. However, the sight was hopeful, for carriers did not travel without escort.

Half an hour later a destroyer appeared on the horizon. It stopped about 200 yards from them, its searchlights playing over the water. Their voices did not carry far enough and the searchlight beams did not happen to fall in their direction. The destroyer turned and faded into the darkness.

The men began to cry, curse and pray. However, Wohlleb spotted an escort destroyer from the opposite direction which came to within 100 yards. A voice came out of the darkness: "Survivors in the water, we hear you but cannot see you. Yell twice if we are to turn right and once if we should proceed straight ahead."

Two loud yells brought the long-awaited rescue with dry clothes, hot coffee and a warm bunk.

THE EXPERIENCE of uss Monaghan (DD 354) was similar to that of Hull and Spence. This is how it appeared to J. C. McCrane, Water Tender Second Class and Robert J. Darden, Machinist's Mate Second Class:

"Before the final roll there were 40 or 50 of us in the after gun shelter. We stopped work and hung on. We began to get scared. All of us were praying like we never prayed before, some of us out loud, too. When it came, someone threw open the hatch and we started to scramble out. Under the circumstances, most of us were pretty orderly. The fellows started helping each other, particularly the shorter men who couldn't reach the hatch."

"I climbed out of the hatch and stood on a bulkhead. The waves were knocking me about, but I didn't want to shake loose because I saw what happened to the men who had jumped as soon as we heeled. Finally a big wave shook me loose and I went scrambling along the ship until I was lucky enough to grab a depth charge rack. I walked along the torpedo tubes. Another wave hit me and I went into the air."

"The next thing I knew I was struggling in the water trying to keep from being pounded against the ship. Water and oil were blowing against my face. I was choking and beating the water with my arms and legs like a puppy. I saw I wasn't getting anywhere so I calmed down and got away gradually, but I was losing strength when suddenly someone yelled: "Hey Joe, grab that raft in back of you." Eventually 13 of us got to it and hung on the sides like they did in a movie I saw."

"About this time Monaghan filled with water and went down. It looked to us as though there was no other raft. We looked around for others to help and helped some of the badly injured to get on the raft."

"Before we got the bottom of the raft down, it turned over four or five times. This meant we had to fish around and help the wounded back, and we were getting pretty weak and tired. After we got the bottom down we all climbed aboard that first night."

"We broke out the emergency rations - canned meat, hard biscuits and stuff like that - and the water. We were limited to a biscuit and a cup of water two or three times a day. As soon as we opened the meat, the sharks started nosing around."

"The next day we were all confident we would be picked up. Planes passed over us but it was still pretty rough and our little raft must have been hard to see. A TBF went right over us. That night a fellow died after he went berserk and started drinking salt water. We tried to stop him, but couldn't. Another fellow started swimming around the raft, and we lost him. Holland and Guio died of injuries."

"The next day and night passed the same way. One man went over the side and was lost and two more swam to an unoccupied raft and were never seen again."

"By the morning of the third day, things were beginning to look pretty grim. Pretty soon we saw some fighter planes come over and knew we were either near land or one of our carriers. Those two planes banked over us and dropped some water markers. Twenty minutes later we saw the most wonderful sight in the world, a tincan steaming at full speed right at us."

For three days ships and aircraft combed the area for missing men. The final total of men rescued included seven officers and 55 enlisted men from Hull, one officer and 23 men from Spence, and the six men from Monaghan. Tabberer, herself dismasted by the storm, had rescued 55 of them. About 790 officers and men were lost or killed, and 80 were injured.

The losses incurred necessitated an inquiry, of course. Why should the three destroyers have been lost, if not the others?

As a result, a circular letter addressed by CINCPACFLT to the Pacific Fleet and naval shore activities concerning the responsibilities of a commanding officer in choosing between seeking safety in a storm and attempting to meet his commitments has become almost a classic. The letter is quoted in Part below:

"The Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, wishes to emphasize that to insure safety at sea, the best that science can devise must be regarded only as an aid and never as a substitute for the good seamanship, self-reliance and sense of ultimate responsibility which are the first requisites in a seaman and naval officer."

"A hundred years ago, a ship's survival depended almost solely on the competence of her master and on his constant alertness to every hint of change in the weather. To be taken aback or caught with full sail on by even a passing squall might mean the loss of spars or canvas; and to come close to the center of a genuine hurricane or typhoon was synonymous with disaster."

"Seamen of the present day should be better at forecasting weather at sea than were their predecessors. The general laws of storms, and the weather expectancy for all months of the year in all parts of the world are now more thoroughly understood, more completely catalogued and more readily available in various publications. But just as a navigator is held culpable if he neglects "Log, Lead and Lookout," through blind faith in his radio fixes, so is the seaman culpable who regards personal weather estimates as obsolete and assumes that if no radio storm warning has been received, then all is well, and no local weather signs need cause him concern."

"The most difficult part of the whole heavy-weather problem is of course the conflict between the military necessity for carrying out an operation as scheduled, and in the possibility of damage or loss to our ships in doing so. For this, no possible rule can be laid down. The decision must be a matter of calculated risk either way. It should be kept in mind, however, that a ship which founders or is badly damaged is a dead loss not only 'to the current operation but to future ones, that the weather which hinders us may be hindering the enemy equally, and that ships which, to prevent probable damage and possible loss, are allowed to drop behind, or to maneuver independently, may by that very measure be able to rejoin later and be of use in the operation."

"But the degree of a ship's danger is progressive and at the same time indefinite. It is one thing for a commanding officer, acting independently in time of peace, to pick a course and speed which may save him from a beating from the weather, and quite another for him, in time of war, to disregard his mission and his orders and leave his station and duty."

"It is here that the responsibility rests on unit, group, and force commanders, and that their judgment and authority must be exercised. They are of course the ones best qualified to weigh the situation and the relative urgency of safety measures versus carrying on with the job in hand."

"It is most definitely part of the senior officer's responsibility to think in terms of the smallest ships and most inexperienced commanding officers under him. He cannot take them for granted, give them tasks and stations and assume either that they will be able to keep up and come through any weather that his own big ship can; or that they will be wise enough to gauge the exact moment when their task must be abandoned. The very gallantry and determination of our young commanders need be taken into account here as a danger factor, since their urge to keep on, to keep up, to keep station, and to carry out their mission in the face of any difficulty, may deter them from doing what is actually wisest and most profitable in the long run."

"The time for taking all measures for a ship's safety is while still able to do so. Nothing is more dangerous than for a seaman to be grudging in taking precautions lest they turn out to have been unnecessary. Safety at sea for a thousand years has depended on exactly the opposite philosophy."

--(Signed) C. W. Nimitz.